Climate change remains one of the most pressing issues facing our planet today. Scientists globally are engaged in extensive research to unravel the complexities of Earth’s climate system, utilizing vast amounts of observational data to create predictive models that span the next century. However, as researchers such as those from EPFL (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne) have noted, not all climate models are created equal. The challenge lies not only in predicting future climate scenarios but also in determining which models are grounded in scientific accuracy and reliability.

The endeavor to model Earth’s climate is inherently complex due to various factors, including the chaotic nature of the atmosphere and the myriad interactions between components such as oceans, ice, and land. The EPFL researchers highlighted a significant issue: around a third of existing climate models fail to accurately reflect observed sea surface temperature data. This raises critical questions regarding the credibility of these models and the narratives they produce. The implications are substantial; if scientists misinterpret data or rely on flawed models, policy-makers may implement ineffective strategies in response to climate change.

Given these concerns, researchers from EPFL implemented a novel rating system that classifies climate model outputs based on their performance against existing data. Their findings elucidate the spectrum of reliability among the models, separating them into three broad categories: those that do not replicate sea surface temperatures well, those that show robustness but lack sensitivity to carbon emissions, and those that are sensitive to carbon emissions and predict a significantly warmer future.

The distinction between carbon-sensitive and non-sensitive models is crucial. Athanasios Nenes, an EPFL professor involved in the study, emphasizes the importance of understanding the implications of carbon sensitivity in climate projections. The more sensitive models suggest an alarming increase in temperatures, providing a stark contrast to estimates derived from less sensitive models, which may inadvertently lull society into a false sense of security.

This disparity reinforces a pressing concern: current mitigation strategies aimed at reducing carbon emissions may not align with the most severe projections from carbon-sensitive models, potentially leaving humanity unprepared for a catastrophically hot future. It underscores the need for an enhanced focus on understanding carbon dynamics in climate modeling—not merely for academic rigor but for the very survival of ecosystems and human communities globally.

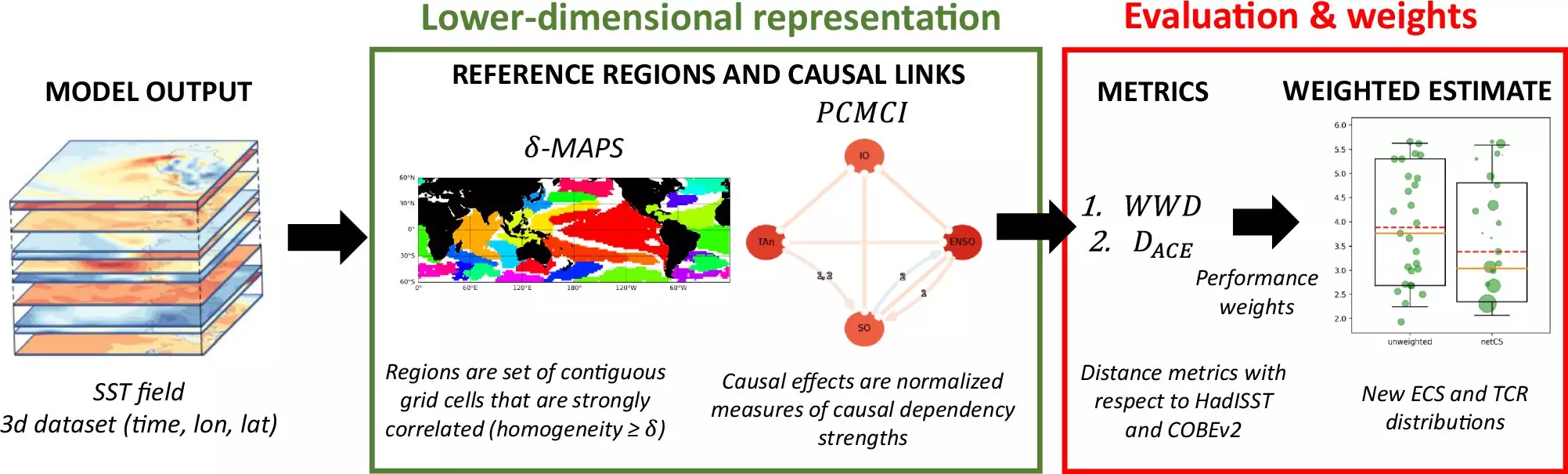

In tackling the challenge of climate modeling, the team from EPFL devised an innovative machine-learning tool named netCS. This sophisticated instrument enables researchers to sift through extensive data sets effectively, streamlining the evaluation of climate models. The ability to analyze terabytes of information rapidly has the potential to revolutionize how scientists assess the performance of climate models, leading to better-informed decisions based on the most reliable simulations.

The introduction of netCS represents a significant leap in the field of climate science. By organizing and evaluating data in a more accessible way, the tool allows scientists to identify which models align best with real-world observations. Moreover, it enhances the overall understanding of climate behavior and provides a clearer picture of the potential impacts of climate change.

One striking facet of the study is the human element shared by Nenes, who reflects on his experiences in Greece, where he has witnessed firsthand the dramatic shifts in climate over the past few decades. The drastic increase in summer temperatures and the rise of natural disasters, such as forest fires encroaching upon urban areas, serve as cautionary tales. These personal accounts emphasize the urgency of addressing climate change and the pain felt by those impacted.

Nenes draws a poignant parallel to the figure of Cassandra from Greek mythology, linking it to the plight of climate scientists. Just as Cassandra’s warnings were unheeded, the voices of climate scientists often struggle to penetrate the layers of public skepticism and political inertia. However, the narrative does not conclude in resignation. Instead, Nenes encourages persistence, suggesting that the imperative for action should galvanize rather than deter scientists and advocates in their mission to combat climate change.

As we step further into the 21st century, the complexities of climate modeling demand our attention more than ever. Understanding the nuances of these predictive models—and discerning which are rooted in credible science—is paramount for establishing effective climate policies. By integrating innovative tools like netCS and fostering a dialogue that transcends disciplines and communities, we can navigate the waters of uncertainty inherent in climate change. Only through concerted effort and informed decision-making can we hope to mitigate the impacts of a warming planet and safeguard our future.

Leave a Reply