Recent findings from Northern Arizona University (NAU) are fundamentally challenging the long-held view that the 4.2 kiloyear (ka) megadrought was a catastrophic global climate event leading to widespread societal collapse. This investigation, which incorporated a comprehensive analysis of over a thousand climate datasets, suggests that while this megadrought occurrence 4,200 years ago did leave its mark, its impacts were not uniform or uniformly severe across the globe. As researchers delve deeper into the complexities of Earth’s climate patterns during the Holocene epoch, which began around 11,700 years ago, they argue that the narrative of the megadrought as a singular, catastrophic event detracts from our understanding of historical climate variability.

The NAU study was not just an academic exercise; it was a product of a unique approach that actively engaged graduate students in research. By creating a course focused on analyzing extensive datasets, the faculty facilitated collaborative learning and discovery. This approach resulted in a diverse team of co-authors, including faculty, students, and alumni, fostering a shared sense of ownership over the study’s outcome. The lead author, Nicholas McKay, emphasized the necessity of a detailed investigation into the megadrought’s validity, particularly after its elevation as a notable geological marker in 2018.

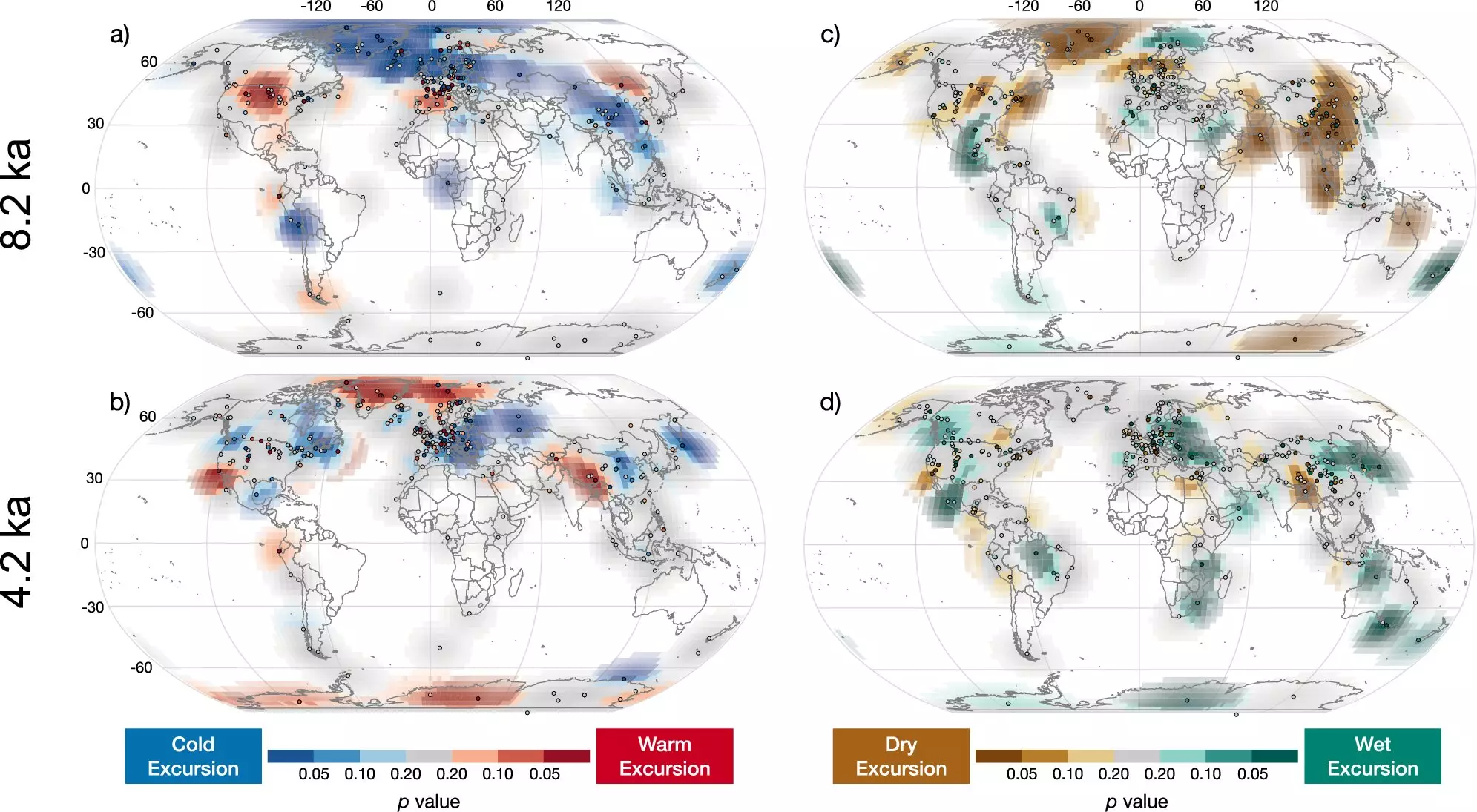

In the process of analysis, the team developed an innovative methodology that significantly enhanced the detection and assessment of climate events in paleoclimate data. By examining fluctuations in temperature and moisture over millennia, they reframed the understanding of these climatic changes as a series of localized events rather than a singular, monumental occurrence. This analytical framework not only allows for a reevaluation of the 4.2 ka megadrought but also sets a precedent for future studies in paleoclimatology.

One of the most compelling takeaways from the research is the realization that climate anomalies in the Holocene are often geographically diverse. Although the 4.2 ka megadrought did correspond with climate shifts in certain regions, these impacts were inconsistent and far less severe than previously assumed. McKay explained that more significant climatic events, such as the 8.2 ka climatic event, were identified, underscoring the notion that abrupt changes have been a common characteristic throughout the Holocene, albeit localized.

This perspective invites a broader discussion about the nature of climate change itself. The notion that distinct regional climatic events do not necessarily translate into global patterns is crucial in understanding natural climate variability. Additionally, the research identified periods of significant climatic fluctuations in later historical contexts, such as during the Dark Ages and the Medieval Climate Anomaly. This critical challenge to the monolithic view of the 4.2 ka megadrought as a central turning point opens avenues for new inquiry into the intricate tapestry of climate history.

Understanding historical climate dynamics can yield invaluable insights for contemporary climate models and predictions. The NAU study underscores that while natural climatic variations can occur at regional scales over century-long timespans, they may not reflect global phenomena. This distinction is particularly relevant in our current context, characterized by human-induced changes in climate spurred by fossil fuel emissions and other anthropogenic factors.

As co-author Leah Marshall articulated, the research urges caution when inferring global significance from local climate changes. The findings indicate that as we advance our climate models, recognizing both historical variability and the unique drivers of modern climate change becomes imperative. This comprehension will not only inform how we perceive past climate events but may also shape the frameworks for future climate forecasting and resilience planning.

This comprehensive examination of the 4.2 ka megadrought is far from merely an academic footnote; it serves as a crucial reminder of the complexity of Earth’s climatic past. The NAU research encourages a more nuanced approach to studying paleoclimate, fostering a synthesis of localized and global perspectives. As we grapple with the implications of climate change today, understanding the historical patterns of climate variability helps us to prepare for the multifaceted challenges that lie ahead. With the lessons gleaned from this study, the academic community is better equipped to investigate climate anomalies and inform future climate policy effectively. Through the collaborative efforts of students, researchers, and educators, a richer dialogue about climate history is not only possible but essential for navigating our evolving environmental landscape.

Leave a Reply