Anorexia nervosa is a profound and complex mental health issue that transcends simple dietary choices and impacts many aspects of life. Defined primarily by intense fear of weight gain, distorted body image, and severe restriction in food intake, this disorder inflicts significant emotional and physical tolls on those affected. It is not just a lifestyle choice, but rather, a serious mental health condition that predisposes individuals to increased risks of anxiety, depression, and malnutrition, necessitating urgent intervention and treatment.

Despite its prevalence and severity, the intricate mechanisms that underlie anorexia are still being unraveled by researchers. A recent study is shedding light on potential neurobiological factors, suggesting that alterations in neurotransmitter function within the brain may significantly contribute to this eating disorder. By investigating how these changes occur, researchers hope to improve treatment strategies and understanding of anorexia’s complex nature.

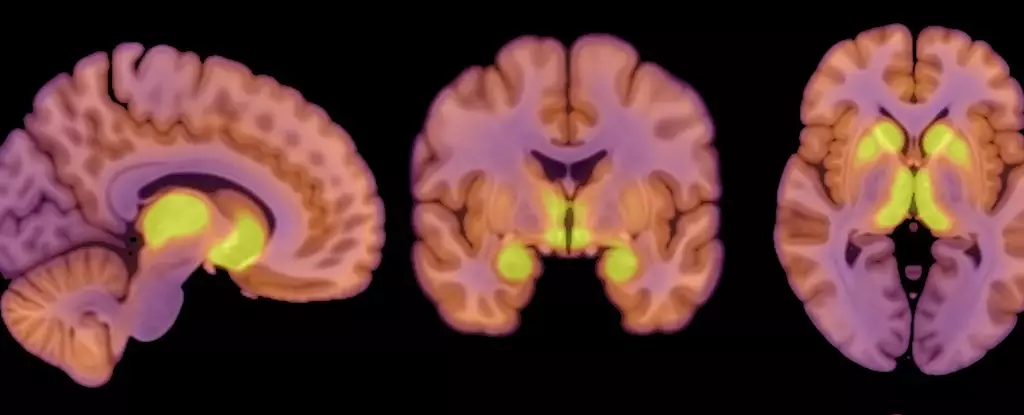

Central to the recent study is the focus on neurotransmitter pathways, particularly involving mu-opioid receptors (MORs). These receptors are integral components of the brain’s opioid system, which plays a crucial role in regulating both appetite and pleasure derived from eating. The researchers noted that individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa exhibit heightened MOR availability in reward-related brain areas, contrasting sharply with what has been observed in obese populations.

Pirjo Nuutila, a co-author on the study and physiologist at the University of Turku, pointed out that this elevation of MORs might explain the distinct appetitive behaviors seen in anorexia patients. Unlike individuals with obesity, who experience reduced opioid activity and corresponding low appetite, anorexia patients struggle with pronounced appetite dysregulation, where the heightened opioid tone may encourage a disordered relationship with food.

In this context, it becomes evident that the neural mechanisms governing eating behavior are far more nuanced than previously understood. The balance between hunger and satiety, pleasure and aversion, is deeply embedded within the brain’s biochemistry, demonstrating the need for continued research in the intersection of neuroscience and psychological health.

The study comprised a small sample of 26 participants, including 13 women diagnosed with anorexia and 13 healthy controls. The patients were relatively homogeneous, with a similar age range and demographic background, which provided a focused lens on the intricacies of anorexia in females. The researchers employed positron emission tomography (PET) scans to illuminate the molecular dynamics occurring within the brains of these individuals, particularly analyzing MOR availability alongside glucose metabolism.

Significantly, the study revealed that anorexia patients, despite their reduced caloric intake, demonstrated a normal level of glucose utilization in the brain. This finding suggests an adaptive mechanism where the brain prioritizes its energy requirements, striving to function optimally even amidst the dire physiological challenges posed by malnutrition. Lauri Nummenmaa, a co-author and cognitive neuroscience professor, highlighted that the brain essentially attempts to safeguard itself against the detrimental effects of low energy availability, reflecting a remarkable but troubling resilience.

While the study presents compelling insights into the neurobiological aspects of anorexia, it is essential to note its limitations. The purely female cohort means that findings might not be generalizable to male populations, where anorexia presentation may diverge significantly. Additionally, the small sample size limits the robustness of conclusions that can be drawn.

The researchers deliberately avoided using questionnaires concerning eating behaviors, cognizant of the sensitivity surrounding such topics in individuals with anorexia. This decision, while understandable, results in a lack of correlation data between MOR availability, glucose metabolism, and eating habits. This oversight raises critical questions regarding the direction of future studies; establishing a clearer relationship between the neurobiological markers and behavioral patterns is essential for holistic treatment approaches.

Furthermore, the causal relationship between the altered opioid system and anorexia remains unspecified, necessitating continued investigation. Is the heightened MOR presence a precursor, a consequence, or a contributing factor to the disorder? The answers to these questions may not only improve intervention strategies but also deepen the understanding of how mental and physiological states intertwine.

The findings from this recent study offer a fresh perspective into the neurobiological foundations of anorexia nervosa, positing that the brain’s opioid system may serve as a pivotal player in the disorder. Yet, as this complex interplay of neurochemistry and behavior is further explored, it becomes increasingly clear that a multidimensional approach is necessary. The myriad factors influencing anorexia necessitate collaboration across various disciplines—psychology, neuroscience, and nutrition—aimed at developing robust treatment models that address both the mental and physical health challenges posed by this devastating condition. This understanding is crucial, as the struggle against anorexia is not merely a battle of willpower, but one requiring comprehensive support and intervention tailored to individual needs.

Leave a Reply