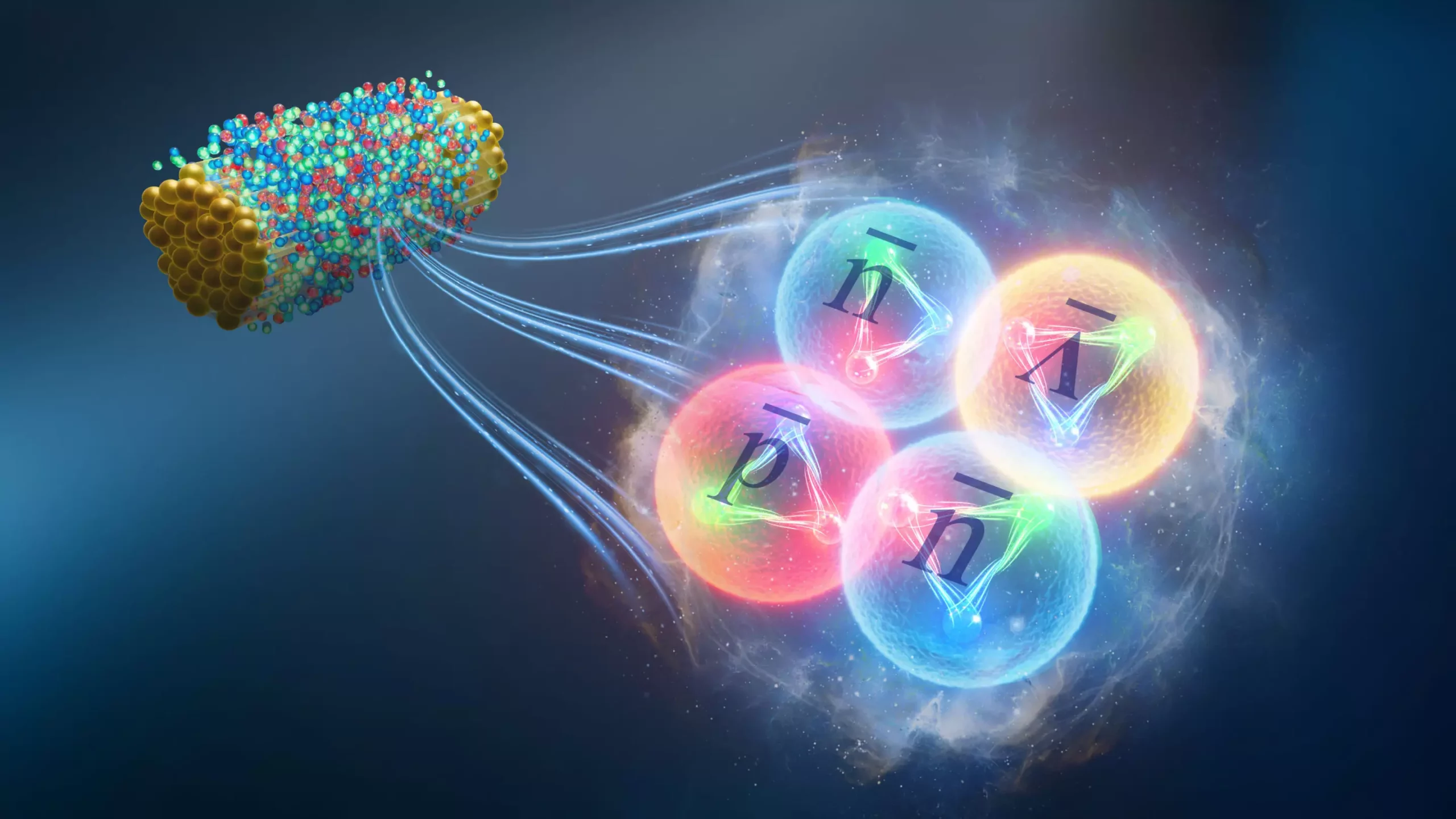

The exploration of antimatter has long captured the imagination of scientists, offering crucial insights into the fundamental workings of the universe. Recent groundbreaking research at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) has brought to light a newly identified antimatter nucleus known as antihyperhydrogen-4. This nucleus, marking the heaviest antimatter specimen detected to date, consists of four specific antimatter particles: one antiproton, two antineutrons, and one antihyperon. The findings, reported by the STAR Collaboration in the esteemed journal Nature, provide a significant leap forward in understanding the elusive properties and behaviors of antimatter in relation to its matter counterpart.

Physics has long grappled with the puzzling dominance of matter over antimatter in our universe. According to the prevailing theories, matter and antimatter were created in equal amounts during the Big Bang approximately 14 billion years ago. Yet today, the visible universe is primarily composed of matter, prompting questions about why this asymmetry exists. Junlin Wu, a doctoral student at Lanzhou University and a collaborator in this research, poignantly encapsulated the dilemma: “Why our universe is dominated by matter is still a question, and we don’t know the full answer.” The RHIC offers a prime environment for such investigations by simulating conditions akin to those of the early universe, allowing researchers to recreate the production of matter and antimatter under high-energy collision events.

The RHIC, operated by the U.S. Department of Energy at Brookhaven National Laboratory, is a sophisticated facility designed to accelerate heavy ions to speeds approaching light. These collisions generate a hot, dense state of matter known as a quark-gluon plasma, akin to the conditions present in the first moments after the Big Bang. This plasma serves as a cauldron for the creation of various particles, including both matter and antimatter. The team’s task, amidst the debris of billions of collisions, is to sift through the chaos and identify rare particles like antihyperhydrogen-4.

The STAR physicists initially verified their ability to detect antimatter by identifying previously known particles such as the antihypertriton and antihelium-4. Building on these achievements, the search for antihyperhydrogen-4 presented a significant challenge due to its inherent instability and the specific combination of particles required for its formation. Finding this exotic nucleus necessitated all four required antimatter constituents—an antiproton, two antineutrons, and an antihyperon—to coalesce in close proximity immediately following the high-energy collision. As physicist Lijuan Ruan remarked, “It is only by chance that you have these four constituent particles emerge from the RHIC collisions close enough together.”

To detect antihyperhydrogen-4, the STAR team meticulously analyzed the particles resulting from the decay of these unstable nuclei. The process involved tracking the paths of decay products, including antihelium-4 and positively charged pions. Utilizing advanced computational techniques, the researchers sifted through a staggering number of collision events, matching decay patterns to isolate those originating from potential antihyperhydrogen-4 formation. Ultimately, this painstaking analysis led to the identification of 22 candidate events, with background noise allowing for an estimation of around 16 genuine antihyperhydrogen-4 detections.

Following their discovery, the STAR Collaboration ventured into the experimental comparison of antihyperhydrogen-4 with its matter counterpart, hyperhydrogen-4. Notably, the scientists found no significant differences in lifetimes between these antimatter and matter particles, reinforcing the stability symmetry that governs fundamental particle interactions. While this might seem unremarkable, it affirms current physical theories, providing a framework within which future antimatter investigations will continue.

The next frontier in this research involves measuring the mass differences between corresponding matter and antimatter particles, an endeavor likely to yield even further insights. Emilie Duckworth, a key contributor to this research, remarked on the significance of their findings as a seed for continued exploration in the domain of antimatter physics. As the understanding of antimatter progresses, it may one day unravel the greatest cosmic riddles, guiding humanity toward answers about the fundamental nature of existence and the mere fabric of our universe.

The discovery of antihyperhydrogen-4 not only stands as a hallmark achievement in modern physics but also reinforces the unwavering dedication of scientists in unraveling the profound mysteries of antimatter, solidifying the critical connection between experimental findings and theoretical physics in the quest for understanding the universe’s enigmas.

Leave a Reply