Methylmercury, a potent neurotoxin, has been increasingly surfacing in discussions related to public health, particularly its detrimental effects on children and adults alike. A recent study conducted by research teams from Harvard University’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, along with associates from the University of Delaware and the University of British Columbia, has shed light on the alarming connection between industrial fishing practices and human exposure to this hazardous compound. This article delves into the findings of the study, analyzing key elements such as fishing practices, seafood consumption, and the broader implications for communities reliant on fish as a primary food source.

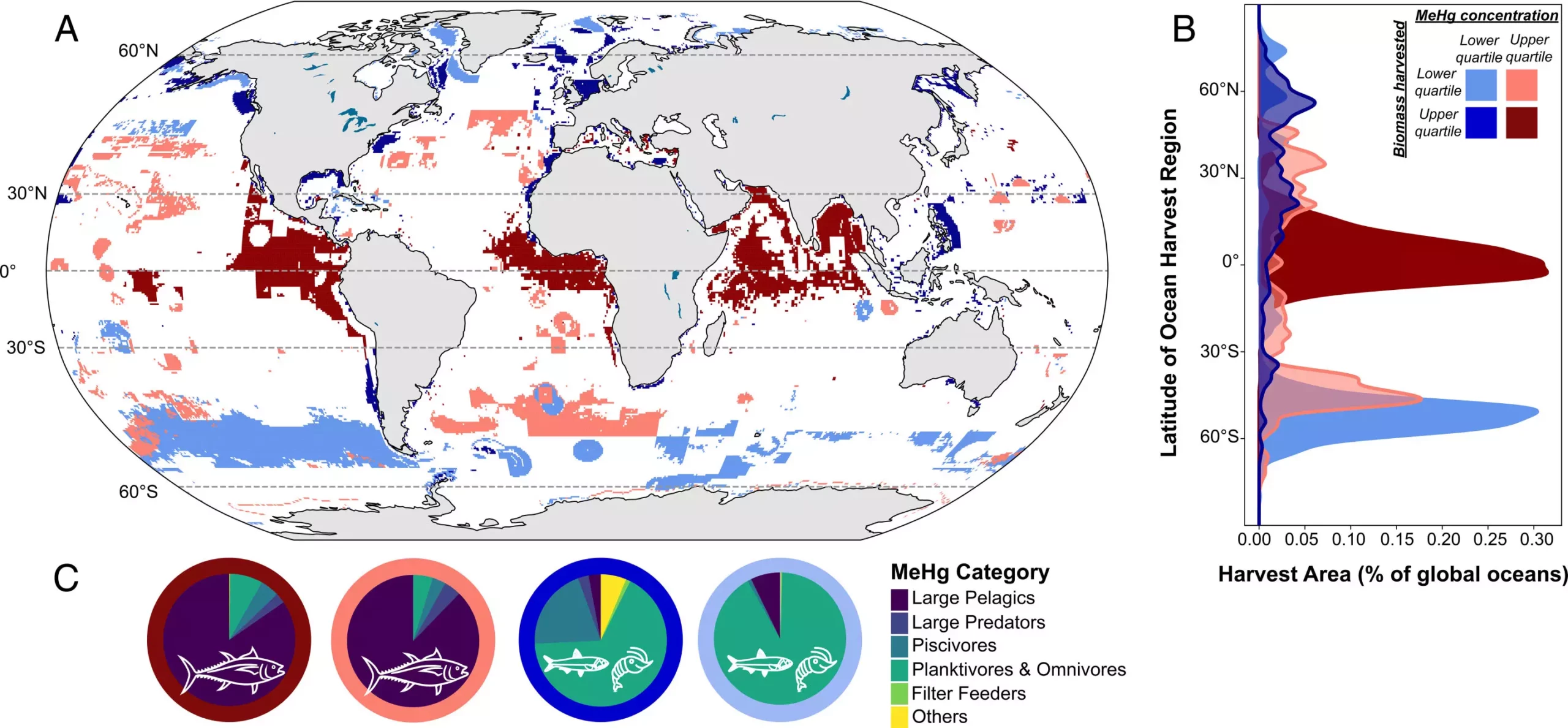

The research highlights a startling fact: over 70% of methylmercury extracted from the ocean is attributed to industrial fisheries that target large fish, especially tuna, in tropical and subtropical waters. The increasing popularity of large pelagic fish can largely be traced back to advancements in fishing technologies since the 1980s. Innovations such as onboard freezing and fish aggregating devices have significantly boosted the efficiency and scale of commercial fishing, making these fish more accessible to the global market. While this may seem beneficial for food supply, the hidden cost is substantial.

The primary concern is that large pelagic fish are notorious for harboring higher levels of methylmercury compared to smaller fish species. This is largely due to a process known as biomagnification, where toxins accumulate as they move up the food chain. As larger fish, such as tuna, consume smaller fish laden with methylmercury, they acquire much greater concentrations of the toxin, presenting a significant health risk to humans who consume them.

Understanding how methylmercury enters marine ecosystems is critical. Sources of mercury emissions include industrial processes—most notably, coal-fired power plants, waste incineration, and mining—together with natural occurrences like volcanic eruptions. This mercury settles into oceans and is transformed into methylmercury by various microorganisms, particularly in warmer waters typical of tropical and subtropical regions. The research posits that the environmental conditions in these locations, combined with industrial fishing practices, have resulted in a “high methylation zone,” amplifying the concentration of methylmercury within top marine predators.

Study author Mi-Ling Li expresses concern over how current fishing practices jeopardize public health, stressing the need for better alternatives. What makes this situation all the more concerning is that populations consuming these large pelagic fish are not just jeopardizing their health due to methylmercury levels alone; they are also missing out on the nutritional benefits that smaller fish typically provide. For example, the essential nutrients found in fish, including omega-3 fatty acids and selenium, are comparatively lower in larger, methylmercury-laden seafood.

The research further explores the implications for subsistence fisheries, which serve as an integral food source for families and communities around the globe. Alarmingly, the study indicates that 84% to 99% of these subsistence fisheries surpass the safe exposure thresholds for methylmercury. Socioeconomically disadvantaged communities that rely heavily on fish for their diet often face serious health ramifications from consuming contaminated seafood, an issue exacerbated by pollution sources over which they have little control.

As Elsie Sunderland, a senior author on the study, notes, these communities are victims of environmental pollution—a phenomenon for which they bear no culpability. It is increasingly important to address the nuances in food systems, as well as the systemic globalization of industrial fishing practices that prioritize large pelagic species over more sustainable options. This knowledge is vital for policymakers and public health officials aiming to improve dietary recommendations and protect vulnerable populations.

In light of the findings, it becomes imperative to rethink our seafood consumption patterns. The study advocates for a shift towards smaller pelagic fish, such as sardines, anchovies, and herring, which not only contain significantly lower levels of methylmercury but are also richer in vital nutrients. By promoting these healthier alternatives, both consumers and policymakers can work together to create a more sustainable seafood market.

The conclusions drawn from this research compel us to reevaluate our relationship with marine food sources and how industrial practices influence not only our diet but also public health. It is clear that without meaningful changes and sustainable fishing practices, the challenges posed by methylmercury will continue to escalate, potentially affecting millions. A collaborative effort across scientific, legislative, and community realms is critical to ensuring a healthier, more sustainable future.

Leave a Reply